Pain is interesting, salient, mysterious. It may feel like it is in one specific place in or on the body. It may feel diffuse, with gradations, or it may seem referred from one area to another. What is happening in the brain and in the body as these spatial aspects of pain are experienced? How much of the causation of pain occurs where we feel it, and how much occurs in the brain? Below is a series of probes and thinking aloud about where pain is, with speculations to stimulate my thinking and yours. I’m not a “pain expert”, nor a bodyworker that heals clients, nor a physiologist with a specialization in nociception, but a cognitive scientist, with clinical psychology training, interested in body phenomenology and the brain. Please do post this essay to Facebook, share it, critique, respond, and comment (and it would be helpful to know if your background is in philosophy, neuroscience, bodywork, psychology, medicine, a student wanting to enter one of these or another field, etc). Pain should be looked at from multiple angles, with theoretical problems emphasized alongside clinical praxis, and with reductionistic accounts from neurophysiology juxtaposed against descriptions of the embodied phenomenology and existential structures. As I have mentioned elsewhere, it is still early in the history of neurophenomenology…let a thousand flowers bloom when looking at pain. We need data, observations, insights and theories from both the experience side as well as the brain side. Francisco Varela aptly described how phenomenology and cognitive neuroscience should relate:

“The key point here is that by emphasizing a codetermination of both accounts one can explore the bridges, challenges, insights, and contradications between them. Both domains of phenomena have equal status in demanding full attention and respect for their specificity.”

We all know what pain is phenomenologically, what it feels like, but how to define it? The International Association for the Study of Pain offers this definition: “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.” Of particular interest to neurophenomenology and embodied cognitive science is their claim that “activity induced in the nociceptors and nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus is not pain, which is always a psychological state.” Good that they do not try to reduce the experience of pain to the strictly physiological dimension, but I wonder how Merleau-Ponty, with his non-dualistic ontology of the flesh would have responded. Pain seems to transgress the border of mind and body categories, does it not? I am slowly biting off chucks of the work on pain at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Lots of provocative angles, including this one:

“there appear to be reasons both for thinking that pains (along with other similar bodily sensations) are physical objects or conditions that we perceive in body parts, and for thinking that they are not. This paradox is one of the main reasons why philosophers are especially interested in pain.”

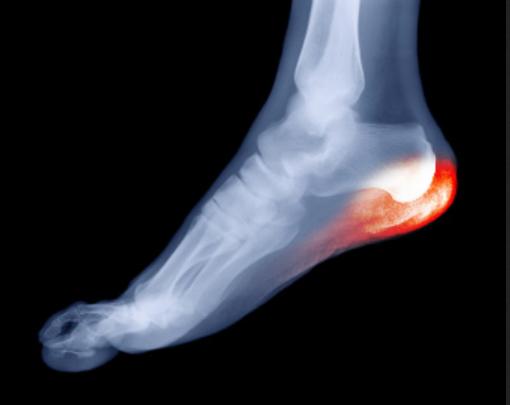

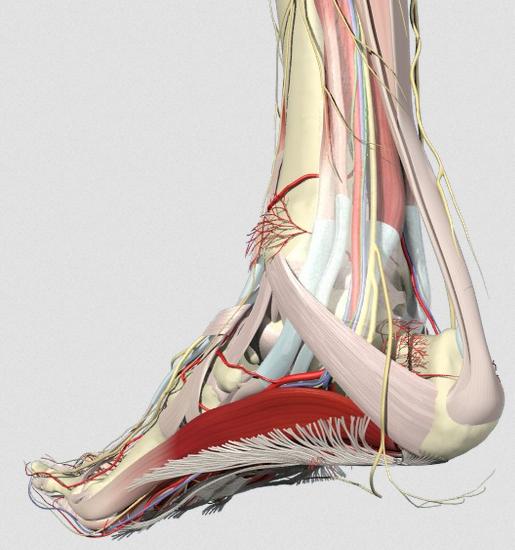

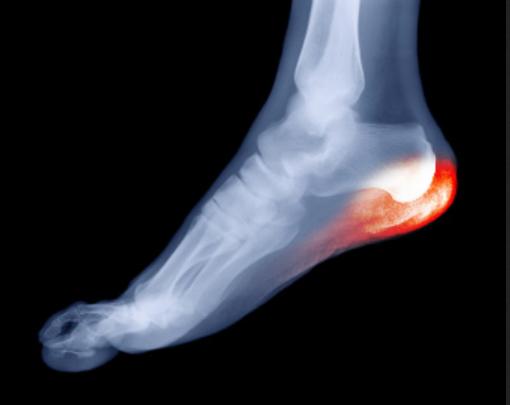

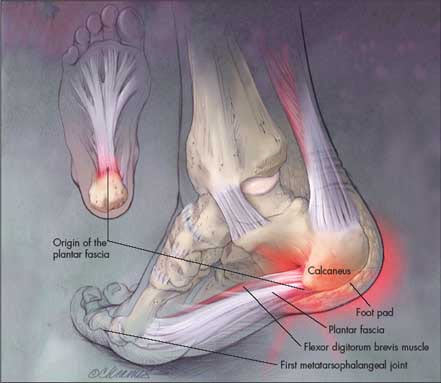

Right now I am particularly interested in the spatial aspect of where pain seems to be, what I might label the spatial phenomenology of nociception. When I introspect on aching parts of my feet, it seems as if the pain occupies a volume of space. Using manual pressure I can find places on my feel that are not sore, right next to areas that are slightly sore, which are in turn near focal areas of highest pain. It seems as if the pain is locatable “down there” in my body, and yet what we know about the nociceptive neural networks suggests the phenomenology is produced by complex interactions between flesh, nearby peripheral nerves, the central nervous system, and neurodynamics in the latter especially. A way of probing this this would be to examine the idea that the pain experience is the experiential correlate of bodily harm, a sort of map relating sensations to a corresponding nerve activated by damage to tissue. So, is the place in my body where I feel pain just the same as where the damage or strain is? Or, Is pain caused by pain-receptive nerves registering what is happening around them, via hormonal and electrical signals? Or is pain actually the nerve itself being “trapped” or damaged, yet in a volume of undamaged tissue one can feel hurts? Could the seeming volume of experienced pain-space be a partial illusion, produced by cognizing the tissue damage as some place near or overlapping with yet not spatially identical to where the “actual” damage is, in other words a case of existential-physiological discrepancy? One scenario could be, roughly, that pain “is” or “is made of” nerves getting signals about damage to tissue; another would be that pain “is” the nerves themselves being damaged or sustaining stress or injury. Maybe pain involves both? Maybe some pain is one, or the other? In terms of remembering how my heel pain started, it’s not so easy, but I love to walk an hour or two a day, and have done so for many years. I recall more than ten years ago playing football in the park, wearing what must have been the wrong sort of shoes, and upon waking the next day, having pretty serious pain in my heel. Here are some graphics that, intuitively, seem to map on to the areas where I perceive the pain to be most focal:

from bestfootdoc.com

from setup.tristatehand.com

from plantar-fasciitis-elrofeet.com

If I palpate my heel, I become aware of a phenomenologically complex, rich blend of pleasure and pain. I crave the sensation of pressure there, but it can be an endurance test when it happens. Does the sensation of pressure that I want reflect some body knowledge, some intuitive sense of what intervention will help my body heal? How could this be verified or falsified? It is not easy to describe the raw qualia of pain, actually. I can describe it as achey and moderately distressing when I walk around, and sharp upon palpating. Direct and forceful pressure on the heel area will make me wince, catch my breath, want to gasp or make sounds of pain/pleasure, and in general puts me in a state of heightened activation. But I love it when I can get a therapist to squeeze on it, producing what I call “pain-pleasure”:

from indyheelpaincenter.com

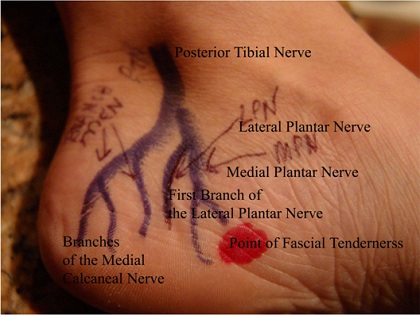

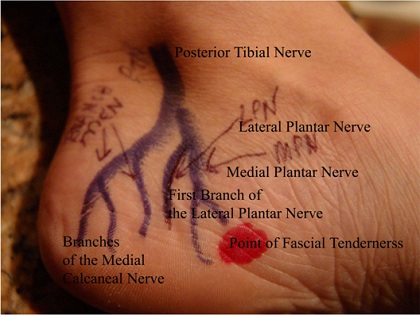

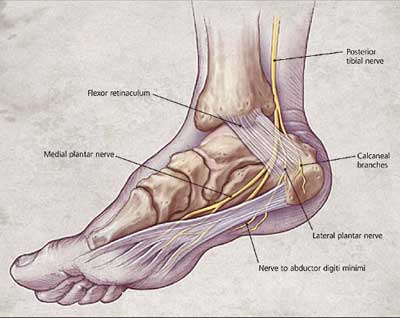

This diagram below helps me map the sensations to the neuroanatomy. We need to do more of this sort of thing. This kind of representation seems to me a new area for clinical neurophenomenological research (indeed, clinical neurophenomenology in general needs much more work, searching for those terms just leads back to my site, but see the Case History section in Sean Gallagher’s How the Body Shapes the Mind).

from reconstructivefootcaredoc.com

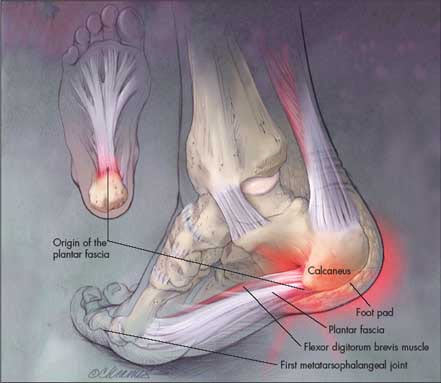

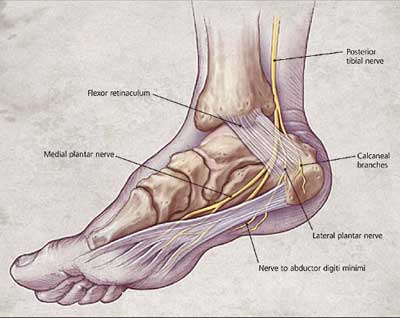

What is producing the pain-qualia, the particular feeling? Without going too far into varying differential diagnosis, it is commonly attributed to plantar fasciitis. There the pain would be due to nociceptive nerve fibers activated by damage to the tough, fibrous fascia that attach to the calcaneus (heel bone) being strained, or sustaining small ripped areas, and/or local nerves being compressed or trapped. A 2012 article in Lower Extremity Review states that “evidence suggests plantar fasciitis is a noninflammatory degenerative condition in the plantar fascia caused by repetitive microtears at the medial tubercle of the calcaneus.” There are quite a few opinions out there about the role of bony calcium buildups, strain from leg muscles, specific trapped nerves and so forth, and it would be interesting to find out how different aspects of reported pain qualia map on to these. Below you can see the sheetlike fascia fiber, the posterior tibial nerve, and it’s branches that enable local sensations:

from aafp.org

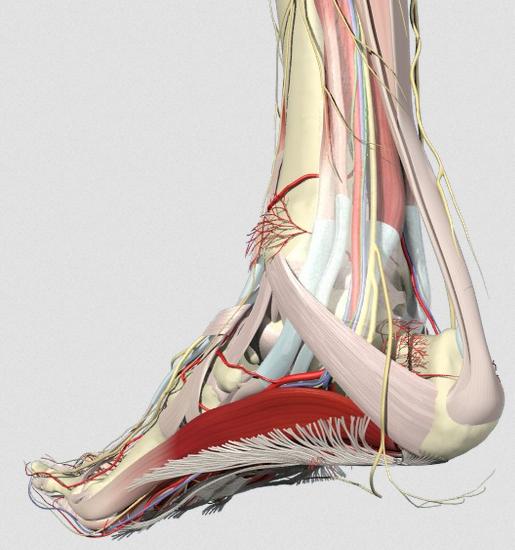

Next: fascia and the innervation of the heel, from below:

from mollyjudge.com

Another view of the heel and innervation:

from mollyjudge.com

Below is a representation of the fascia under the skin:

from drwolgin.com

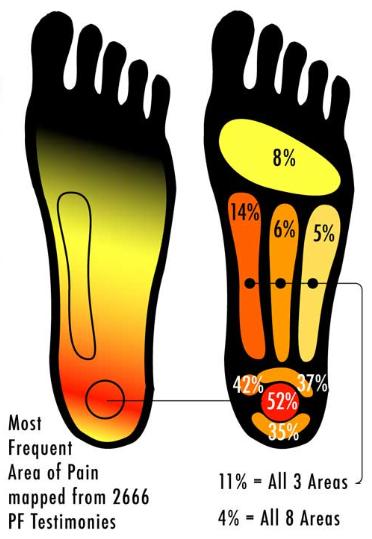

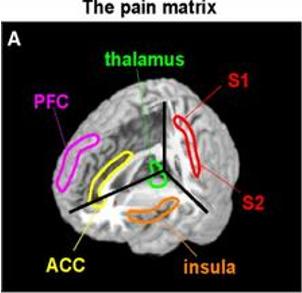

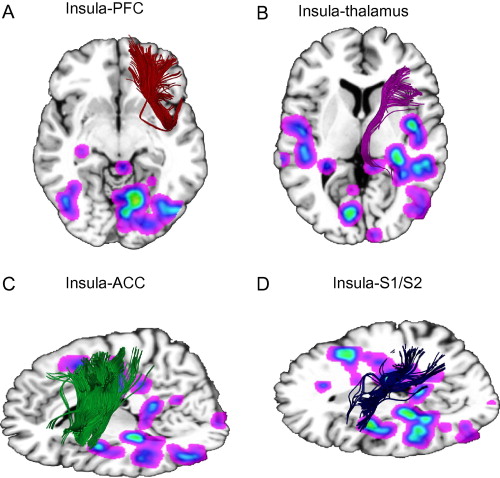

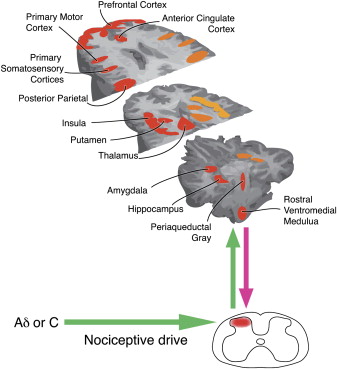

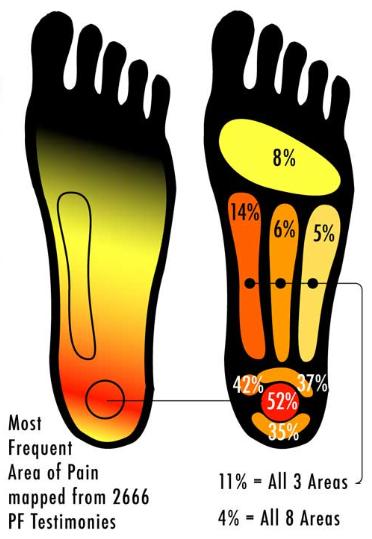

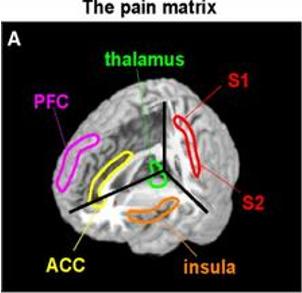

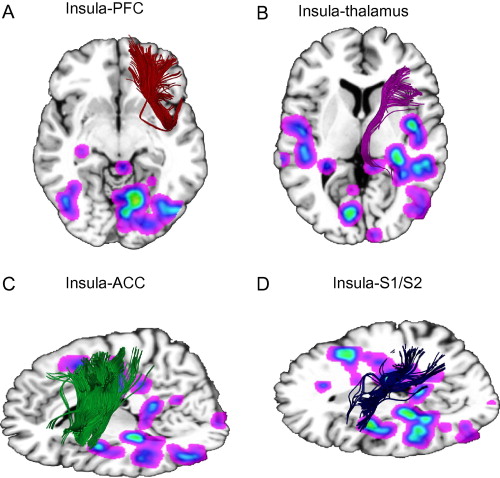

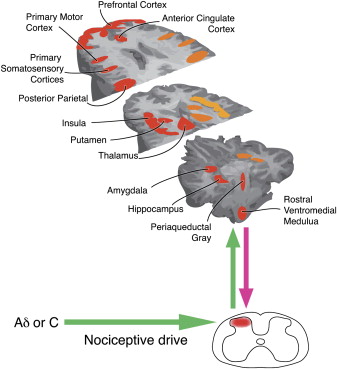

There is a very graphic,under the skin, maybe not SFW surgeon’s-eye perspective on these structures available here. Heel pain turns out to be very common, and is evidently one of the most frequently reported medical issues. Searching online for heel pain mapping brings up a representation purportedly of 2666 patients describing where they feel heel pain:  I can’t find where this comes from originally and can’t speak to the methodology, rigor, or quality of the study, but the supposed data are interesting, as is the implicit idea of spatial qualia mapping: the correspondence of experienced pain to a volume of space in the body. It also quite well represents where the pain is that I feel. The focal area seems to be where the fascia fibers attach to the calcaneus, an area that bears alot of weight, does alot of work, and is prone to overuse. So, where is the pain? Is it in the heel or the brain? Is it in the tissue, the nerve, or both? Is there a volume of flesh that contains the pain? I am going to have to think about these more, and welcome your input. What about the central nervous system that processes nociceptive afferents coming from the body? A good model of pain neurophenomenology should involve a number of cortical and subcortical areas that comprise the nociceptive neural network: -primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and secondary somatosensory cortex (S2): -insula -anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) -prefrontal cortex (PFC) -thalamus Here are some representations of the pain pathways, or the nociceptive neural network:

I can’t find where this comes from originally and can’t speak to the methodology, rigor, or quality of the study, but the supposed data are interesting, as is the implicit idea of spatial qualia mapping: the correspondence of experienced pain to a volume of space in the body. It also quite well represents where the pain is that I feel. The focal area seems to be where the fascia fibers attach to the calcaneus, an area that bears alot of weight, does alot of work, and is prone to overuse. So, where is the pain? Is it in the heel or the brain? Is it in the tissue, the nerve, or both? Is there a volume of flesh that contains the pain? I am going to have to think about these more, and welcome your input. What about the central nervous system that processes nociceptive afferents coming from the body? A good model of pain neurophenomenology should involve a number of cortical and subcortical areas that comprise the nociceptive neural network: -primary somatosensory cortex (S1) and secondary somatosensory cortex (S2): -insula -anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) -prefrontal cortex (PFC) -thalamus Here are some representations of the pain pathways, or the nociceptive neural network:

from Moisset and Bouhassira (2007)

Moisett el (2009)

from Tracey and Mantyh (2012)

Broadly speaking, pain seems to be generated by tissue damage, inflammation, compromising the integrity of tissue, stress on localized regions, and so forth being processed by peripheral afferent pain pathways in the body, then phylogenetically ancient subcortical structures, and then the aforementioned cortical regions or nociceptive neural network. As I have mentioned many times, making a robust account of how various regions of the brain communicate such that a person experiences qualia or sensory phenomenology will need to reference neurodynamics, which integrates ideas from the physics of self-organization, complexity, chaos and non-linear dynamics into biology. It is gradually becoming apparent to many if not most workers in the cognitive neurosciences that there are a host of mechanisms regions of the brain use to send signals, and many of these are as time dependent as space dependent. Michael Cohen puts it thusly: “The way we as cognitive neuroscientists typically link dynamics of the brain to dynamics of behavior is by correlating increases or decreases of some measure of brain activity with the cognitive or emotional state we hope the subject is experiencing at the time. The primary dependent measure in the majority of these studies is whether the average amount of activity – measured through spiking, event-related-potential or -field component amplitude, blood flow response, light scatter, etc. – in a region of the brain goes up or down. In this approach, the aim is to reduce this complex and enigmatic neural information processing system to two dimensions: Space and activation (up/down). The implicit assumption is that cognitive processes can be localized to specific regions of the brain, can be measured by an increase in average activity levels, and in different experimental conditions, either operate or do not. It is naïve to think that these two dimensions are sufficient for characterizing neurocognitive function. The range and flexibility of cognitive, emotional, perceptual, and other mental processes is huge, and the scale of typical functional localization claims – on the order of several cubic centimeters – is large compared to the number of cells with unique physiological, neurochemical, morphological, and connectional properties contained in each MRI voxel. Further, there are no one-to-one mappings between cognitive processes and brain regions: Different cognitive processes can activate the same brain region, and activation of several brain regions can be associated with single cognitive processes. In the analogy of Plato’s cave, our current approach to understanding the biological foundations of cognition is like looking at shadows cast on a region of the wall of the cave without observing how they change dynamically over time.” But what of the original question? Is pain where you feel it in the body, or in the brain? It seems to me the answer must be both. The experience of pain being localized there or a little on the left is a product of local tissue signals and receptor activation, which produces peripheral afferent nerve firing, which gets processed by spinal afferent neurodynamics, brainstem activation, thalamic gating, and then somatosensory, insular, anterior cingulated, and prefrontal cortical regions. Yet the real model of pain, one that invokes mechanisms and causes, remains elusive. And a good model of pain must account for the possibility of pain without suffering as well! For now, what I can offer are probes to get us speculating, thinking critically, and eventually building a clinical neurophenomenology of pain. If that interests you, by all means get involved.