(Part II is here, and Part III is here)

I will attempt in three essays to outline the sweep of ideas, researchers, and works that lead a few of us to speak of “neurophenomenology” as a more or less distinct field. Part I traces 19th century psychology, neurology, and phenomenology roughly up to World War II. Part II examines the impact of cognitivism, the continued development of clinical neurology and basic neuroscience, the progression of phenomenological thought in psychology and medicine, and criticisms of cognitive science. Part III explores the early 1990’s origins of the emerging field of neurophenomenlogy within the broader context of interest in embodied cognition and consciousness studies. Any corrections, suggestions, or criticisms are welcome.

It may be too early to attempt a definitive characterization of the constitutive elements, at the least it is a combination of clinical studies by neurologists, psychiatrists, and psychologists, experimental work on the brain and mind, and philosophical analysis of consciousness and cognition. While the term “neurophenomenology” has a recent (early 1990’s) origin, the project of understanding the mysterious and profound relationship between brain events and awareness goes back at least as far as classical Greek philosophy. Physicians and philosophers have grappled with the enigma of existence and of consciousness for millenia. Psychology has roots in medicine, ethics, and the philosophy of mind and epistemology, but by the late 19th century, the overlapping fields of biological psychology, psychiatry, behaviorism, and the psychophysiology and psychophysics of perception emerged. We can trace the series of research traditions that eventually developed into “neurophenomenology” in the 1990’s through ideas and practices of 19th century researchers. Understanding how these traditions drew from various sources, and subsequently interacted, requires we situate each field in then-current European disciplines. Elites were schooled in the Gymnasia, and acquired a broad and deep education before later specialization. Physicians and/or laboratory experimentalists were expected to be familiar with classical and to an extent modern philosophy, and gentleman scholars would dabble in but also contribute to numerous fields: highly unlike the current hyper-specialization of academia. Psychology was very pluralistic at this stage: not yet fully divorced from philosophy, still possessing a sense that a field focusing on the richness and complexity of the human psyche must involve a study of consciousness.

There were numerous German psychophysics and psychological researchers looking for how consciousness and the brain were related, such as Herman von Helmholtz (1821-1894), Gustav Fechner (1801-1887), and Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920). Much effort was expended on rigorously correlating physiological and psychological measurements, resulting in establishing thresholds of perception and the limits of just noticeable differences. A number of laboratories used experimental methods where subjects told researchers what they were perceiving through verbal reports based on introspection.

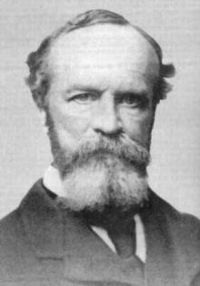

Bold innovators like the justly renowned philosopher, psychologist and physician William James (1842-1910) also looked for the physical basis of experience. He pioneered research into neurology, performed psychological experiments, and made creative, yet disciplined, investigations into experiential aspects of mind. James’ use of crisp, lucid language describing consciousness and awareness pushed the threshold of what science, psychology, and philosophy could say about consciousness. James helped establish American experimental psychology, but really hit his stride with his still-fresh writings. He described how memory and the enigmatic quality of the moment-by-moment flow of experience, and even wrote about altered states of consciousness. His central concept of consciousness being like a stream is still influential, and there is now a renewed appreciation for his work on how emotions are coupled to the physiological state of the body. All in all, he is probably the most important figure in the history of American psychology. Yet his interdisciplinary boldness, penetrating curiosity and at times virtuostic powers of description of complex mental phenomena were not easily replicated by those researchers and younger colleagues he influenced.

William James, master theorist of consciousness

In the Principles of Psychology, James provided an admirably straightforward account of what introspection is:

“Introspective observation is what we have to rely on first and foremost and always. The word introspection need hardly be defined – it means, of course, looking into our own minds”

Fin-de-siecle psychophysics was in its golden years during his time, and while James’ wrote admiringly of the “philosophers of the chronometer” and other technically adroit experimental psychologists in his lab that measured perception and other phenomena, James himself continued his project of probing and describing the phenomenology of consciousness itself. While considered a father of introspectionist psychology and a forefather of both behaviorism and cognitive neuroscience, perhaps because of his hard-to-imitate brilliance, James did not leave a school of younger researchers to follow through on his research into consciousness.

In America, Europe, and Russia, generations of research into the organic basis of pathologies was reaching new heights of explanatory power. The German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin (1856-1926) was formulating sophisticated theories of the physiological basis of mental illness in the early 20th century, in retrospect a crucial step in the early development of the now accomplished field we know as clinical neuropsychology. After each war, neurologists noted the correlations between location of trauma to the brains of the injured with deficits in speech, memory, movement, perception, affect, emotion,and “body knowledge”. The Russian tradition culminated later in the influential work of Alexander Luria (1902-1977).

The force of new findings in clinical studies, physiology, and experimental laboratory research eventually produced a scientific psychology that established itself as independent from moral philosophy, epistemology, metaphysics, and the philosophy of language. The success of 19th century psychophysics and neurophysiology, with breakthroughs such as Hermann von Helmholtz‘s (1821-1894) measurement of the speed of the nerve impulse, provided ample justification for the fissure. Psychophysics experiments painstakingly produced data on the “just-noticeable difference” in light or stimulus intensity, etc. but there were real difficulties in establishing a consensus between the different laboratories on methodologies for dealing with subject’s reports on their perceptions.

While towering figures like Ernst Weber (1795-1878), Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920), and Edward Titchener (1867-1927) were establishing a canon of principles and techniques for psychology, it proved extremely difficult to come up with one standard way to operationalize measurements that involved verbal reports about subjective judgments and conscious experience. For all the brainpower deployed in various laboratories, by the 1930’s the tide was turning against scientific research into consciousness due to the influence of behaviorism, which reacted against the lack of an agreed-upon methodology in the German psychophysics-based psychology, especially involving introspection. The behaviorists marshaled an impressive array of experimental measurements techniques to establish causal relationships between stimulus and response, and then to infer lawlike generalizations. They stringently opposed the use of any mental concepts as inherently subjective and thus unscientific, and eschewed using first-person reports as much as possible. Within fields like the psychology of visual perception it was necessary to get verbal reports from subjects, but the behaviorists strove mightily to build a scientific psychology on purely physical principles. But if the behaviorists’ reacted against psychophysics for being insufficiently liberated from concerns with cognitive processes, others argued precisely the opposite. The philosopher Franz Brentano (1838-1917) wrote Psychology From An Empirical Standpoint in 1874, where he popularized the notion that the contents of experience constituted an important field of inquiry in their own right. Brentano’s influential theories of intentionality stressed the need to investigate the contents of awareness and their constitutive operations. Researchers working on cognition who were dissatisfied with the limitations of psychophysics ,and unpersuaded by the soon-to-be dominant anti-mentalist strictures of the behaviorists (such as physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) and psychologist/advertising specialist John Watson (1878-1958)) rallied around this line of inquiry. Brentano made an impact among philosophers and psychologists and certain influential clinicians, and in some sense there is a diverse “School of Brentano“.

Arguably the most influential among the students and followers of Brentano was the mathematician and philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859-1938). Husserl was fascinated (obsessed?) with the foundations of logic, mathematics, epistemology, and cognition. Convinced by direct criticism from the celebrated logician Gottlob Frege (1848-1925) that psychological principles were epistemologically inadequate to foundationalize mathematical and logical truths, Husserl would eventually synthesize Brentano’s research into the primacy of intentional awareness within cognition with a quest for the undoubtable (or “apodictic”) core principles of mathematics, logic, and philosophy. After producing light-reading classics such as Philosophie der Arithmetik, he developed a research program into the first principles of cognition, logic, and epistemology called phenomenology. While Husserl attracted many philosophers and certain psychologists to his cause with the 1900-1901 publication of the highly influential Logical Investigations, his continual probing of the constituent ideas underlying mathematical and logical truth was to an extent a solitary quest.

His acolytes and disciples found the Logical Investigations of great importance, yet they did not take up Husserl’s overarching project of a securing a logical foundation for all science, math, and philosophy. In the case of Martin Heidegger, phenomenology was redefined as the means for a still more fundamental investigation into ontology.

Edmund Husserl: logician, philosopher, and phenomenologist

Before WWII Husserlian phenomenology was perhaps the most important development in European philosophy, and influenced a number of other fields, such as psychology and medicine.Because his phenomenology took conscious experience as a source of data (following Brentano) many researchers interested in consciousness and cognition were excited by Husserl’s radically rigorous approach and penetrating exploration of how mental processes constitute, shape, and structure the phenomena of which we are aware. His notion that cognition actively constructs the contents of awareness (compare to Jacob von Uexkull‘s (1864-1944) notion of the umwelt) would be familiar to modern cognitive neuroscientists but to early 20th century psychologists and philosophers was revolutionary. Husserl influenced the philosophers Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), and Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961), the logician/mathematician Kurt Godel (1906-1978), the philosopher-theologian Karol Wojtyla (1920-2005), as well as (in more recent years) the prescient critic of Artificial Intelligence philosopher Hubert Dreyfus, and the cognitive neuroscientist Francisco Varela (1946-2001).

In America and Britain, these developments in Continental thought were generally of no interests to the behaviorists, who aside from biologically/medically-based critiques of the sort offered by neurologist Karl Lashley (1890-1958), enjoyed near-hegemony in scientific psychology. But eventually, the rise of computers led to the “cognitive revolution” : the development of symbolic or information-processing theories of the mind that did not respect orthodox behaviorist’s strictures against the use of mental concepts. In time, this willingness to use mental concepts again would open the door to the study of consciousness in psychology and neuroscience . After WWII, the introduction of computers led to cybernetic, information-processing, symbolic-logical, and representational models of language, memory, behavior, reasoning, and even awareness.

(Part II is here, and part III is here)